This article is about the Dunkirk Memorial in France which commemorates over 4,500 soldiers of the British Expeditionary Force who have no known graves. It will also explain how you can research those commemorated on the memorial. This is one of a series of articles I’ve written to help you research those who served in the British Army:

I also offer a Second World War Soldier Research and Document Copying Service.

The Dunkirk Memorial

The Dunkirk Memorial commemorates 4509 soldiers of the British Expeditionary Force who died between 10 January 1940 and 23 December 1945 and have no known grave. Most of those commemorated on the memorial died between 10 May and 2 July 1940. The British Expeditionary Force began to land in France in September 1939 but there was very little fighting until 10 May 1940. Only four soldiers commemorated on the memorial died between January and April 1940 and I wouldn’t be surprised if they actually died after 10 May. Most of those commemorated on the memorial died between 10 May and 20 June 1940. The Dunkirk Memorial also commemorates those soldiers of the British Expeditionary Force who died while prisoners of war and have no known graves. There are 173 soldiers who died between 1 July 1940 and 23 December 1945 commemorated. Of the soldiers commemorated on the memorial, 4504 served with the British Army and five with the Indian Army. The Indian soldiers were serving with the 22nd Animal Transport Company when they were taken prisoner and died in German captivity.

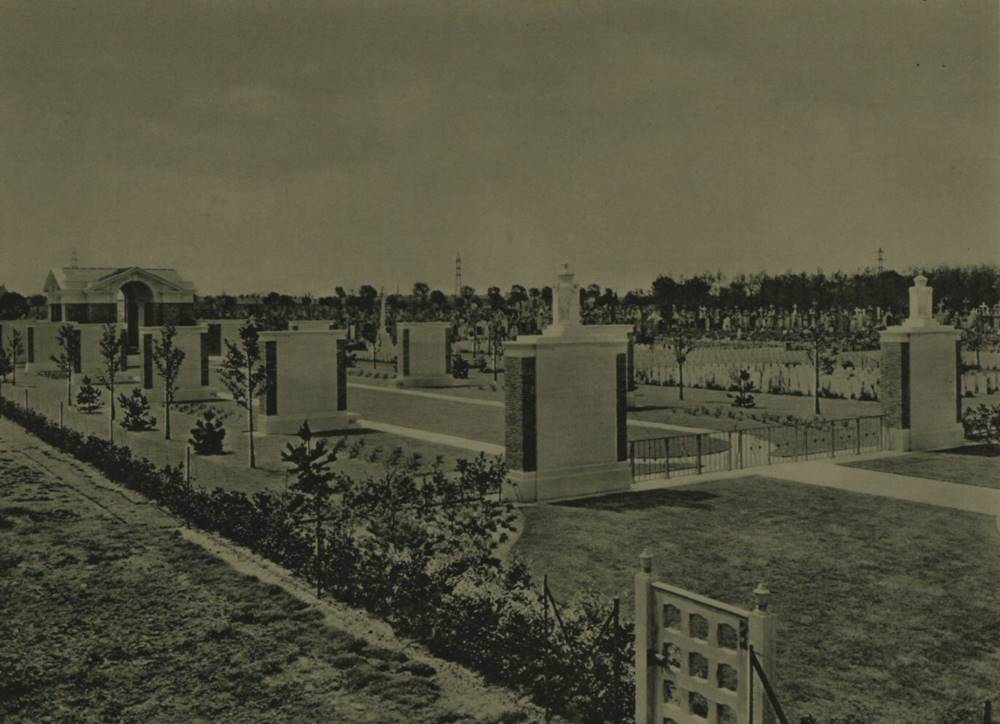

The Dunkirk Memorial was designed by Philip Dalton Hepworth who designed a large number of Second World War cemeteries and also the Bayeux Memorial. On 27 June 1957, the memorial was unveiled by the Queen Mother in front of a large crowd which included hundreds of relatives of the missing. The Dunkirk Memorial is adjacent to the Dunkirk Town Cemetery which contains over a thousand burials from both world wars. Many of those commemorated on the memorial are buried as unknown soldiers in the cemetery. The memorial is dominated by a shrine which is shown in the above photograph. There are two stone columns on either side of the gate surmounted by a Greek urn. In English and French, these columns record:

Dunkirk

Here beside the graves of their comrades are commemorated the soldiers of the British Expeditionary Force who fell in the campaign of 1939-1940 and have no known grave

Either side of the path which leads to the shrine are stone columns which record the names of the missing on Portland stone panels. The missing are listed by their corps or regiment, then rank and alphabetically. Each panel is numbered and if you’re looking for a specific soldier, you can find out which panel they appear on in their Commonwealth War Graves Commission entry. In the shrine is a large engraved stained glass window designed by John Hutton depicting the evacuation.

Researching a Soldier Commemorated on the Dunkirk Memorial

The first step is to look up a soldier’s entry in the Commonwealth War Graves Commission’s website. Each soldier commemorated on the Dunkirk Memorial will have an entry. The exact information recorded will vary, but will usually include:

- Their name

- Rank

- Army or Personal number

- Regiment or corps

- The exact unit they were serving with in that regiment or corps

- When they died

- Information relating to their next of kin

- Any honours or awards

The exact date of death for many of the soldiers commemorated on the memorial is unknown. For example, Private Gordon Noel Salmon 2nd Battalion Royal Norfolk Regiment is listed as having died between 10 May and 22 June 1940. Others have smaller ranges, with Rifleman Sam Taylor recorded as dying between 29 May and 2 June 1940. With further research, you can often narrow down the dates a soldier was killed.

With a soldier’s number, you can order a copy of their service record from the Ministry of Defence or National Archives. They hold the service record of all those commemorated on the Dunkirk Memorial apart from the five Indian soldiers who died as prisoners of war. No death certificate is needed to order these files as the soldiers died in service nor do you need the permission of the next of kin. A service record is important as it will list all the units a soldier served with and when, along with a lot of other important information not found elsewhere.

Once you have a soldier’s number, search for them in the War Office’s casualty lists available on Findmypast. These will list if a soldier was reported missing, killed in action, died of wounds, missing believed drowned etc. While a soldier’s Commonwealth War Graves Commission entry will usually record what unit they were serving with at the time, they don’t always. Some of these soldiers will have their unit recorded in the casualty lists. After you find out which unit a soldier was serving with, you can turn to its war diary to find out what was happening on the day a soldier died or went missing. A war diary was written by an officer and recorded its location and activities. They will usually record when the unit suffered casualties and the circumstances in which they occurred. I offer a copying service for these documents held at the National Archives in London.

If you can’t view a copy of the relevant war diary, then you can see if a regimental or unit history was produced. Most infantry regiments produced a history during the war but you won’t find any histories for most non-combatant units e.g. the Royal Army Service Corps, Auxiliary Military Pioneer Corps. In these cases, a war diary is usually the only source of information.

After a war diary, I’d recommend looking at enquiries into missing personnel held at the National Archives in the WO 361 series. There are ninety-two files covering the missing of the British Expeditionary Force, with the files covering either a ship which was sunk, a regiment or corps, a specific unit or a type of unit for a corps. For example, there is a general file covering enquiries into the missing of the Royal Warwickshire Regiment and also separate files for the Regiment’s 2nd, 1/7th and 8th Battalions. While all the enquiries into missing soldiers of the Durham Light Infantry can be found in a single file. What makes these documents so important is they often contain eyewitness statements of the last sightings of soldiers who went missing in action. The following are typical examples. I’ve changed the names of both soldiers who died and are commemorated on the Dunkirk Memorial:

Missing Personnel, 2nd Battalion The Northamptonshire Regiment British Expeditionary Force, France and Flanders

Major D. J. B. Houchin, M.C. of this unit states:

Lance-Corporal Smith belonged to the Carrier Platoon in France in 1940. At Maroeil village near Arras on 23rd May his section was sent to protect my left flank. During the morning their section withdrew. The carrier of Lance-Corporal Smith ran into shellfire on entering the village, and the crew dismounted. The commander was killed, one member Private Bines was wounded, and Lance-Corporal Smith was severely wounded in the stomach.

Corporal Freestone, now serving with this Battalion, passing in another carrier, took Private Bines on to the regimental aid post and left Smith propped against the side of his carrier, to be collected later. He doubts if Smith could have lived long. Later in the day I passed this spot and saw a dead man propped against a carrier with, as far as I can remember, another dead man near. Private Bines was in England last March

12 December 1942

British Expeditionary Force, France: Northamptonshire Regiment; missing men: WO 361/64.

Signalman Jones G. B. was attached to 2nd Norfolks with No.11 Set, we were in communication from 4th Infantry Brigade H.Q. with the Norfolks and during the early morning the area was under extremely heavy mortar and shell fire. The Operator sent back many S.O.Ss. for support but we were unable to get any. At the latter stages all the personnel of the Battalion Headquarters were fighting it out with German Infantry, and the operator said then over the air that they were completely cut off. They said shells were bursting all around, and suddenly in the midst of conversation they went off the air, and we called but never got any reply. Presumably they had been hit by a shell or mortar. They were in a house in a cellar, but the house had practically been smashed except for the cellar. Information received from the Padre of 2 Norfolks whom I met in Halifax that the Signal Officer of the Battalion was officially a prisoner of war.

British Expeditionary Force, France: Royal Corps of Signals; missing men: WO 361/107.

Another important source of information for those commemorated on the Dunkirk Memorial are local newspapers. These often reported a soldier going missing and later being declared dead. They are the best bet if you’d like to find a photograph of a soldier. A small number of newspapers have been digitized and are available to search on Findmypast. The best newspaper archive in the country is the British Library and you can order copies of the newspapers to its reading rooms in London. Most take 48 hours to arrive from storage so can’t be read on the same day. This photograph is of Driver Stewart Malcolm of the Royal Army Service Corps who was reported to have drowned on 11 June 1940 and is commemorated on the Dunkirk Memorial. It was published in The Courier and Advertiser on 1 August 1940, one of the newspapers available to view on Findmypast.